In the previous editions of From the Devil’s Coach House, I told you a little about the work placement element of my language course, particularly my little stints at La Garage Hermétique and Kerwax. In this issue, I thought I’d fill you in on what happened once school was out.

L’histoire

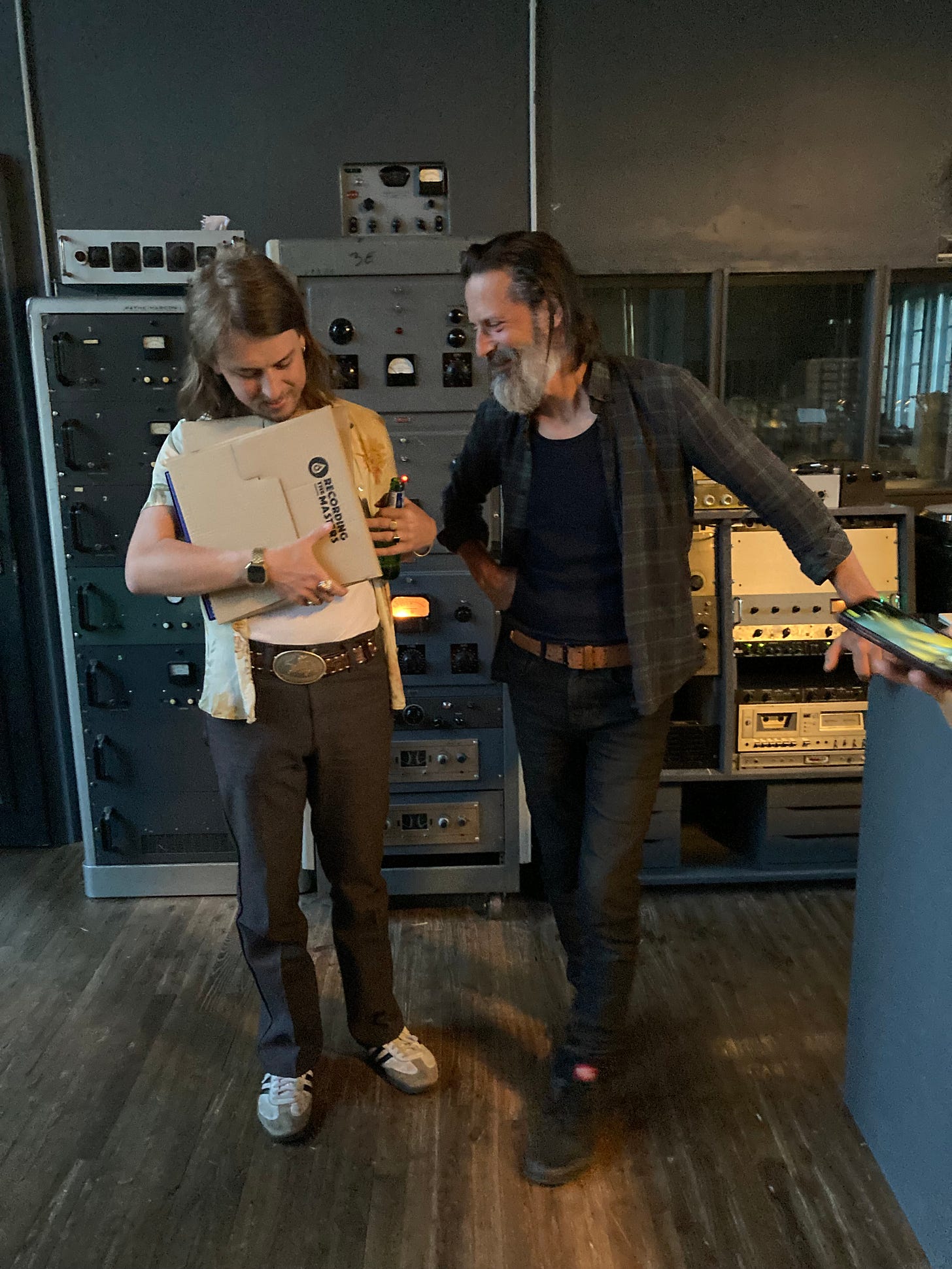

After my quite short stage (work placement) at Kerwax, Christophe invited me to come back and work as tape op for the recording of the latest DeWolff album, Love Death & In Between that was to be recorded live to 24-track tape in May 2022.

Tape op, short for ‘tape operator’, is a job that doesn’t really exist any more, outside of places like Kerwax. Back in the days of analogue studios, tape op was the first “real” job an aspiring, young engineer could get that was a step up from making tea and sweeping the floor. Originally, the tape op would be where the huge, noisy tape machines were housed, in a separate room to the other engineers. The job itself consisted mostly of loading tapes and pressing record/rewind/fast forward/play. However, the tape op did get to see the senior engineer and producer set up the sessions and work with the musicians. From this vantage point, the tape op learnt the trade of audio recording, and, assuming they didn’t mess up too badly, they, themselves, could graduate to recording engineer. Later, the role expanded somewhat, and tape ops became known as assistant recording engineers.

Legendary engineers, such as The Beatles’ Geoff Emerick, started out as tape ops, so I was pretty excited to get such a rare opportunity to follow in his footsteps.

The DeWolff sessions, themselves, were a real masterclass in how things used to be done and what, in many ways, has been lost with digital recording. For the majority of the album, there were eleven musicians playing in the room: guitar/vocals, drums/vocals, organ, bass, piano, percussion, trumpet, sax, trombone and two backing vocalists. The entirety of the album was recorded pretty much live with an incredible vibe that was the combination of the musicians being inspired by the wonderful surroundings of Kerwax and the heritage of the gear there, along with the excitement of the musicians being finally able to get into the same room together and play, after the enforced solitude of the pandemic lockdowns. You can get a small sense of the fun of the sessions from the videos that were shot there.

The sessions were a real coming-together of like-minded creatives. It felt as if Kerwax had been created solely for the purpose of recording this album, and it was incredibly moving to see how happy both the musicians and the engineers were with the results they were achieving.

I guess I did pretty well, as Christophe invited me to came back and work on another album at Kerwax, but this time promoted to recording engineer. It was also nice to see how DeWolff credited me on the record.

“Recording Assistant and tape operator: Steve “he’s always fucking right” Kilpatrick”

The next album I got to work on at Kerwax was Witchthroat Serpent’s Trove of Oddities at the Devil’s Driveway. I have written about those sessions previously on my blog.

The Madeleine

Making recordings using techniques considered retro, or old-fashioned, depending how you look at it, got me to remembering another old teacher of mine.

Before I started my degree at the University of Salford, I actually did an HND in Popular Music and Recording at Wigan and Leigh College. Initially, I started that course because I had no formal training in music and lacked the knowledge and skills to start a degree programme at the time. Once it got going, though, the course was actually very good, and I got to study with some excellent teachers, like Gary Boyle of Isotope and Soft Machine, Paul Mitchell-Davidson and Trefor Owen.

Gary “Genius” Boyle (guitar) performing with Soft Machine

I also had some great classmates. One who stands out particularly was Rob Trotman. For any old metalhead reading this, Rob was the lead guitarist of one of the UK’s greatest Thrash Metal bands, Onslaught.

The college also had a brand-new, state-of-the-art, digital recording studio, which I think may have been a first for a UK FE institution. However, the one thing they were lacking was anyone to teach recording.

Initially, we would just attempt to fend for ourselves in the recording studio. This sometimes consisted of something useful, although was just as likely to involve using the flying faders on the console to convince a younger student that the studios where haunted.

In one of our sessions, we were attempting to record drums for a song, and, in these pre-internet days, were trying to copy from memory a recording session someone had seen on TV. We probably had sixteen mics on the kit, in all, and it sounded terrible. Absolute pants, and we couldn’t work out why.

It was at this point that Keith Bateson, the piano teacher, wandered into the session and asked us what we were up to. After we explained, he responded with, “Pfft, I could get a better sound than that with one mic.”

“Go on, then”.

“Ok, I’ll show you how I used to mic Ringo up at the BBC.”

What? Sorry? Ringo at the BBC?!

Then, he proceeded to mic up the drum kit with a single Shure SM57, and it did, indeed, sound light years ahead of the recordings we had been making.

It turned out that Bolton lad Keith Bateson had been a recording engineer at the BBC in the sixties and had been a preferred engineer of Brian Epstein and his four boys whenever they recorded sessions there.

Ticket to Ride as Recorded by Keith Bateson at the BBC.

I learnt a lot from Keith. After finding out his history as a BBC recording engineer, the college put him in charge of teaching us how to record. What was fantastic about Keith’s recording classes is that they were also history lessons. The reason he had got so good at recording drums with one mic was because that was how many they had spare to use on a session when he started recording The Beatles. In our next lesson with Keith, he demonstrated how he would later use two mics on the drum kit. This quantum leap in recording came about because the BBC invested in some more mics, opening up a whole new world of recording drums with two mics! This is how I learnt recording, through the same process he had developed in the sixties. The lessons were based on the basic principles of using one’s ears, knowing microphone polar patterns and being willing to experiment. It was a great foundation to build on.

The Toys

I recently was gifted an early ‘70s Star drum kit by my lovely friend and talented audio engineer Steeve (that’s right, double “E”) from Raven Black Records.

Star, later in the ‘70s, became the Tama drums that we know today. I’m planning on making some videos demonstrating some of the recording techniques I learnt from Keith. Let me know in the comments if that is something you would find interesting.

And, Now, the End is Near

Thanks for reading another episode of From the Devil’s Coach House. Please let me know in the comments if there is anything you’d like me to talk about more.

Stay noisy!

Steve